by Stefanía Cardonetti

In 2022, the Museum of Immigration in Buenos Aires opened an exhibit “From the Eastern Mediterranean to the Río de la Plata”. It aims to make visible the ethnic and religious diversity that existed and exists in Argentina, in part due to the arrival of immigrants from many parts of the world. Although Italians and Spaniards were the two largest groups that came to the country, it is also true that in 1914 there were almost 600,000 foreigners who were not Italian or Spanish. In the long history of immigration, Argentina was nourished by the arrival of people from various places that came to influence the local social, cultural, and economic life of the host society. That was the case for many Christians, Muslims, and Jews from the eastern Mediterranean who are the protagonists of this exhibit and whose earliest records date from the 1860s. The reasons for emigration were many, but violence towards religious minorities and social tensions produced by the policies of the late Ottoman Empire – in the eyes of whose who arrived in Argentina – were reasons to leave.

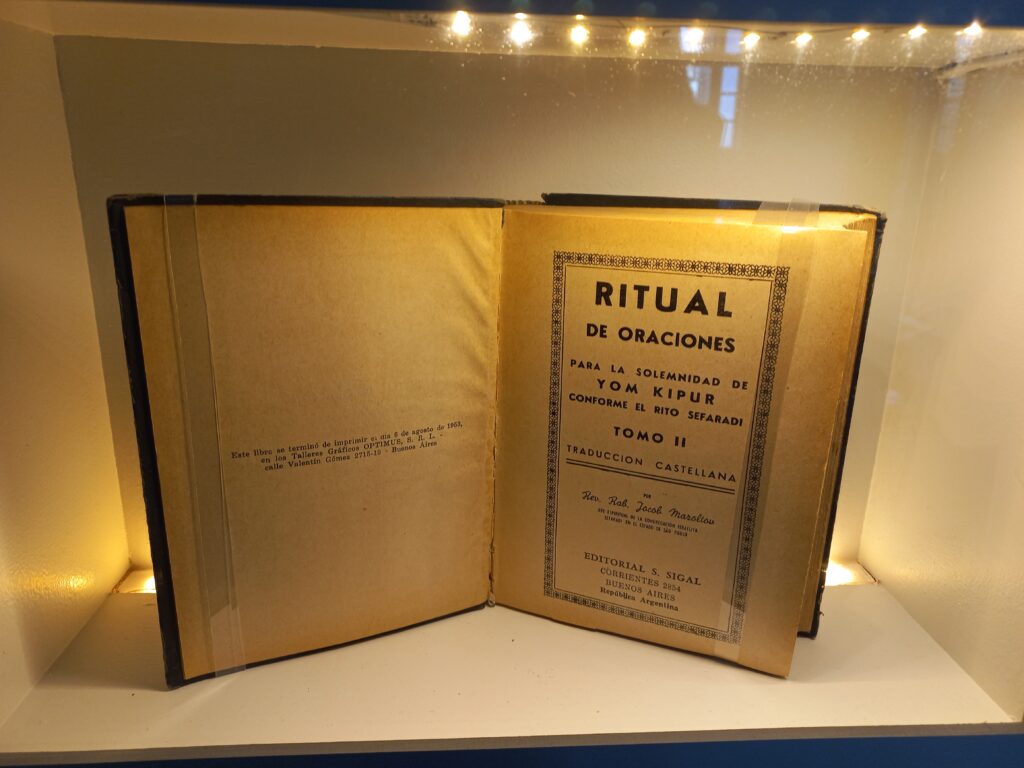

Much of this display was built with objects that were donated by the descendants of immigrants. Among other things, these objects show one of the most important ways that new immigrants integrated into local society: work. In this article, we delve into two topics of this exhibit that illustrate the lives of Arabic-speaking immigrants. Through these objects, we will explore the trajectories of two people, Azur and Abraham, to learn a little more about their journey.

Permit issued by the Province of Buenos Aires to work as an ambulant vendor

The document that appears in this photograph was donated to the Museum of Immigration by an anonymous person. In one display case, visitors can see the permit that Abraham Chama received from the province of Buenos Aires and that enabled him to work as an ambulant vendor.

A common job of many Arab immigrants in Argentina was street vending, popularly known in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as working as a “mercachifle” (hawker). Legally, being authorized to trade as a mercachifle meant being able to sell different products. However, as could be read in the popular magazine Caras y Caretas, whether these migrants worked illegally or legally with such a permit, a large part of society at the beginning of the twentieth century believed that it was a profession that created a negative image for the country. Argentine observers criticized the way these foreign vendors dressed, the way they worked, and the way they occupied public spaces with their carts and merchandise. These portrayals of immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean did not coincide with the aspirations of Argentine ruling elites, who imagined an ideal immigrant living in an agricultural settlement or taking up a trade. Various negative stereotypes emerged about these “Turks”, as they were often erroneously called.

In a process of upward social mobility, those itinerant vendors, like Abraham, who held a permit and had managed to save money could become “bolicheros”, which meant having a shop. This process, as was the case for many migrant groups, relied on social networks through which information circulated about how to develop a business, how to apply for a work permit, how to receive loans, and how to find a place to live on arrival.

Although the work of ambulant vendors or small shopkeepers were among the most common forms of work among Arabic-speaking immigrants, especially for those from present-day Syria and Lebanon, there were other forms of labor integration. Performing music was another, illuminating form of integration. On the one hand, it was something that other immigrants valued because it brought them together through a sense of a common heritage. On the other hand, it could attract a new local audience.

“Black Eyes.” A record by Azur Chami

The record above is one example of the role of music for immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean. Azur Chami was a Syrian-born immigrant from a Jewish family. When he arrived in Argentina, he founded an orchestra with traditional instruments. In addition to being a source of income in a new country, his music was also a way of displaying different identities, related to the local society and his country of origin. In this sense, Azur’s work to compose a new version in Arabic of “El Humahuaqueño”, a typical song from northern Argentina and commonly used in annual carnivals, is revealing.

El Humahuaqueño by Azur Chami (1962)

Music brought Azur several awards in Argentina, and he toured the country along with other immigrant musicians. In so doing, in addition to making a living from this trade and dazzling a new audience, Azur displayed Arabic-language music as an expression of ethnic identity. He preserved his language and his clothing, but at the same time, he contributed to turning the country into a multicultural space. The Museum of Immigration invites visitors to put on headphones and immerse themselves in this musical fusion.

Finally, it should be noted that this exhibit proposes the recognition of migrants such as Abraham and Azur as a restorative practice. When they arrived, they were members of a group that caused concerns among Argentine ruling elites who dreamed of populating the country with people from northern Europe. Many immigrants from the eastern Mediterranean were the object of xenophobic discourses and practices, and some were prohibited from entering the Hotel of Immigrants. Immigrants like Abraham and Azur are not part of the classic national narrative that links European immigration to a founding myth of the country. However, these people also managed to find their way in Argentina and had an impact.