Alina Silveira

(Universidad Nacional de Quilmes/Universidad de Buenos Aires)

On August 11, 1825, the ship Symmetry arrived in Buenos Aires, bringing a contingent of Scottish and English settlers. Recruited by Scottish merchants John and William Parish Robertson, they were the first group of organized families to immigrate to the country to establish an agricultural “colony”, a term widely used in nineteenth-century Argentina to describe a small, somewhat-contained agricultural settlement and community.

Since 1810, successive governments in the Río de la Plata region wanted to promote immigration. However, the wars of independence and internal conflicts made it difficult to carry out systematic plans. Those years of political and economic instability did not create a propitious climate for potential immigrants.

This changed in 1820 under the government of Martín Rodríguez and his minister Rivadavia, when a stable and modernizing power emerged in Buenos Aires that promoted economic growth and crafted an immigration policy that drew attention in Europe. Especially in Great Britain the advances of the Industrial Revolution pushed adventurous merchants to seek new markets and opportunities in the former Spanish colonies. In 1824, an Immigration Commission was created, and it sought to encourage the creation of both agricultural and mining colonies. On that first commission, among others, were the Robertson brothers.

On February 2, 1825, a Treaty of Friendship, Navigation and Free Trade was signed between the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata and Great Britain. The government in London recognized the sovereignty of the political authorities of Buenos Aires and the government in Buenos Aires recognized the civil and commercial rights of British subjects as well as freedom of worship. In this context, several companies aimed at promoting immigration were created, but only the “colony” organized by the Robertson brothers just outside the city of Buenos Aires, in what is now the Partido de Esteban Echeverría, came to fruition.

(January 1825-December 1827) / Source: Archivo General de la Nación, 1825

Families, single men and women, and children all came to the Robertson brothers’ settlement. These were farmers, farmhands, cattlemen, milkmaids, and artisans, and there was also a gardener, a doctor, an architect, a clergyman, and a teacher. The farmers brought with them essential tools and goods (ranging from cutlery and crockery to weapons and soaps).

In Monte Grande, a land covered with thistles and a few huts awaited them. Over the course of four years, they cleared the land, fenced it off and farmed, built houses with bricks made in the same town, bought draft horses, milk cows and sheep for wool, planted hundreds of fruit trees, built a woodworking shop, a blacksmith, a barn and a mill. The butter and cream produced in the settlement was sold in the city of Buenos Aires and surrounding towns. In 1828, more than 500 people lived in the colony. Most of the Scottish settlers were educated, could read, write and do basic arithmetic and were familiar with Scottish literature. Attached to their roots, they remained united by faith, usually married amongst themselves and retained and reconstructed cultural elements of their place of origin. It was common in the colony to hear to bagpipe music, see typical Scottish dances with their distinctive kilts, and attend the local Presbyterian church.

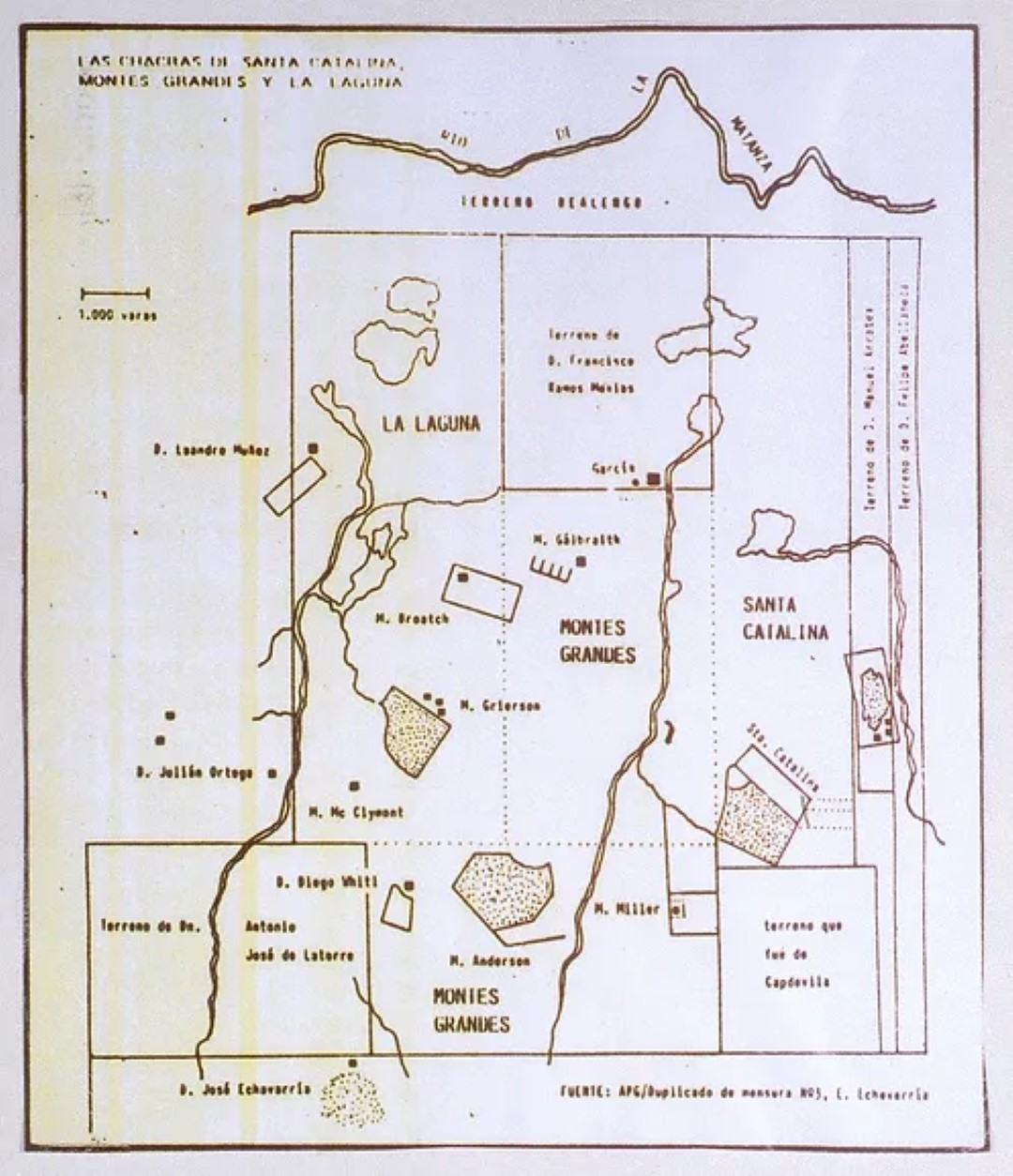

Image 3: Map of the plots at the Estancia Santa Catalina where the Scots’ Colony was located / Source: City of Esteban Echeverria. ca. 1825

Despite its auspicious beginnings, the settlement did not last long. During their voyage aboard the Symmetry, as one of the colonists W. Grierson mentions, differences emerged between English and Scots and between farmers and servants. These conflicts were accentuated in the community, as mentioned by W. Grierson’s granddaughter Cecilia Grierson and the Scotsman James Dodds. Farmers, who were a minority of the settlers, saw themselves as superior and more important, and they made their viewpoint clear to others who had come in search of equality and social advancement. In turn, servants and farmhands denounced these landholders for not living up to the promises made before departing. Landholders accused the Robertson brothers of not living up to the terms of the agreement, while the Robertsons denounced the local government for not assisting them financially. In this context, many servants and laborers abandoned the colony soon after arriving.

Image 5: Hugh Robson. One of the passengers on the voyage of the frigate Symmetry / Source: Archivo Histórico Club San Andrés de Ex Alumnos, in approximately 1850

The colony also turned out to be unprofitable, and the income it generated was not enough to cover the costs of its creation. Perhaps, as Dodds suggests, this was a consequence of the colonists’ imperfect knowledge of the land (including of Argentine seasons and local customs), which led them to try to reproduce Scottish forms of production. Experience with Scottish dairy cows proved of little help with the wilder cows that the settlers found in the Pampas. In turn, their production of butter and cream for local markets were not in high demand amongst consumers who were more accustomed to vegetable oils.

Financial difficulties were compounded when the Robertson brothers deviated from the original contract by refusing government-provided land and instead purchased land near the city, increasing the costs of setting up the colony.

Other external factors compounded these internal difficulties, such as the drought of 1828-29 and the nearby dispute with Brazil for control of Uruguay. Local governments could not provide financial support to the colony, while the land where it was located was devastated by the fights between Unitarians and Federals and some settlers were victims of robbery and murder.

By 1829 the community had been dissolved, and its founders were financially devastated. However, this did not imply failure for the settlers, and some moved to the city and found work as builders and craftsmen while others leased new agricultural land nearby. Others prospered by founding transportation companies (such as the Whites or Bells) or starting new farms (such as the Robsons, Browns, Griersons, or Grahams). Yet not all enjoyed this kind of success. Some returned to their homeland and others fell into alcoholism and destitution.

Further reading

- Dodds, James, Records of the Scottish Settlers in the river Plate and their Churches, Buenos Aires, Grant and Sylvester, 1897.

- Grierson, Cecilia, Colonia de Monte Grande. Primera y única colonia formada por escoceses en la Argentina, Buenos Aires, Taller Jacobo Peuser, 1926.

- Hanon, Maxine, Diccionario de Británicos en Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Gutten Press, 2005

- Stewart, Iain A. D., Two accounts by early Scottish emigrants to the Argentine. From Caledonia to the Pampas, Trowbridge, Cromwell Press, 2000.