Michael Goebel,

Freie Universität Berlin

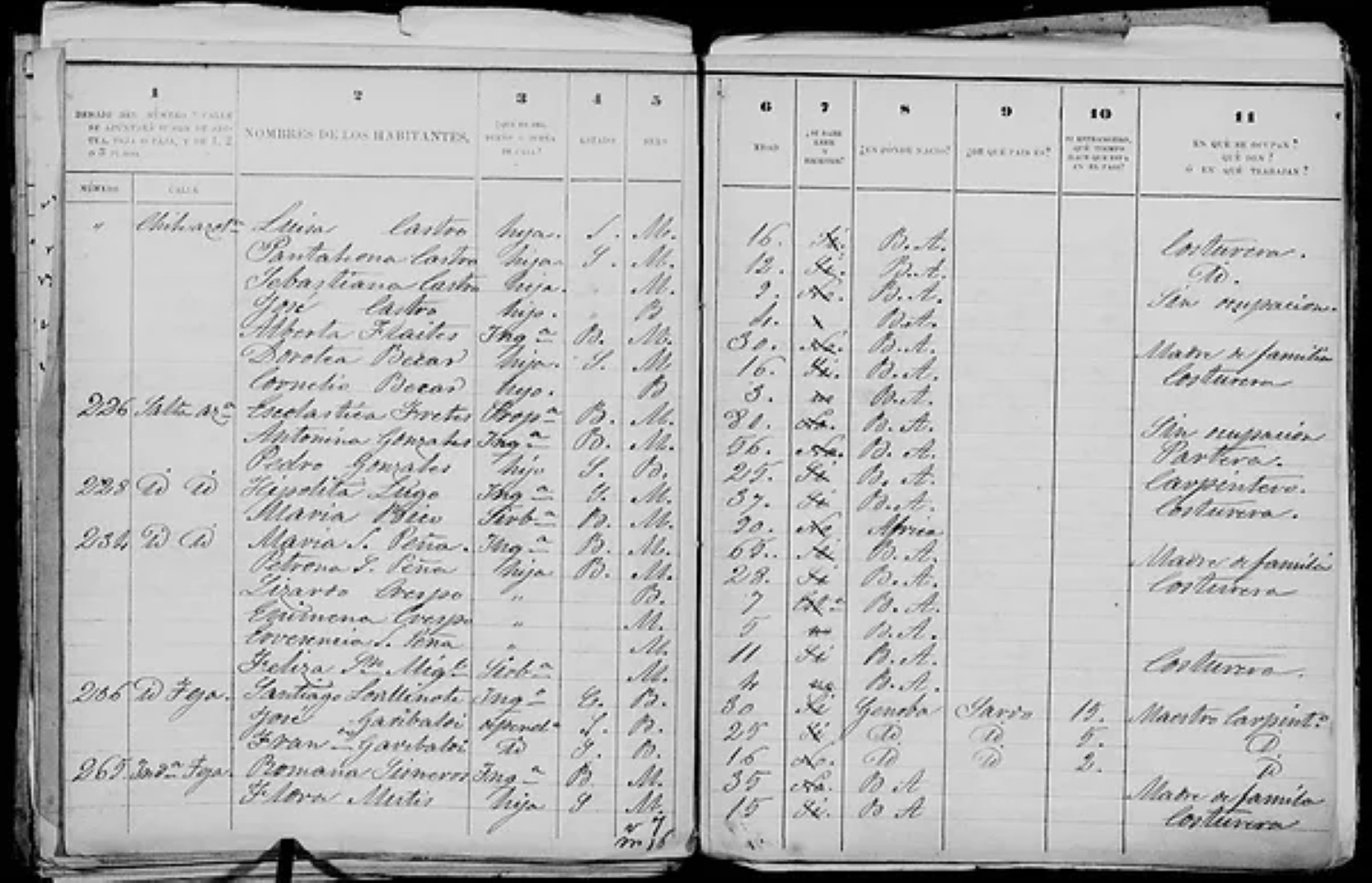

Whatever the reputation of Argentina’s archives, few countries possess a comparable wealth of detailed demographic sources for the nineteenth century. Originally buried at the Archivo General de la Nación, and more recently digitized in part by the Mormon website familysearch, the original sheets of several nineteenth-century censuses are preserved. Historians, if they use censuses at all, are for the most part obliged to content themselves with summary tables published in book forms. Yet individual sheets – completed by each census taker as they walked a city’s streets – contain a wealth of information. Allowing us to look at each individual and into every household, they constitute a marvelous source for – among many topics – the study of Italian migration to Argentina.

What can we learn from these materials? For one, that Italian migration to Argentina prior to its massification with the introduction of steamship navigation was not all that Italian. With our team at the SNSF-funded research project Patchwork Cities, we compiled Excel and Stata databases of the 79,825 individuals recorded in the parish census of Buenos Aires of 1855. With the help of QGIS, we then started mapping. Of the 1855 inhabitants of Buenos Aires, 8,340 were born in what later became Italy, making Italians the largest foreign-born group at that stage. But since the census sheets, at least for more than half of these foreign-born residents, also listed birthplaces in Europe (see figure 1), we can map much more precisely the municipalities of birth of all European-born people in the Buenos Aires census of 1855 (see map 1). As it turns out, “Italians” were in their vast majority from Liguria (around 70 percent), Piedmont (around 15 percent), and Lombardy (around 10 percent).

Municipal Birthplaces in Europe of the European-born in the Parish Census of Buenos Aires of 1855 (where that municipality was recorded and identifiable, i.e. in roughly 65 percent of all cases). One dot represents one person. Note that the visualization overemphasizes rural areas where the dots are relatively spread out, such as the Basque Country, and underemphasizes cities with many emigrants, such as Genoa.

Source: All maps created by the Patchwork Cities project

Although the particular importance of the Italian Northwest in the early stages of Italian migration to Argentina are somewhat known, the magnitude of this dominance is rarely appreciated. Even if Map 1 instantly reveals how few migrants to Buenos Aires came from Central and Southern Italy prior to 1855, the map masks another aspect of the geographic concentration of emigration: In assigning one dot to each person found in the census of Buenos Aires of 1855, it overrepresents small rural places of origin. Instead, it underestimates the overwhelming importance of the city of Genoa. Map 2 instead shows the 28 most common European birthplaces found in the 1855, giving each of them a circle of a size depending on how often each city was mentioned as a birthplace: 3,591 times, it turns out, a little more often than the next 27 combined. Evidently, this enormous Genoese presence owed much to the earlier trading connections studied by Catia Brilli.

Map of the 28 most commonly listed birthplaces in Europe in the Buenos Aires census of 1855. The size of the circle represents the number of times the birthplace was listed. Note the importance of port cities overall and of Genoa in particular.

Port cities also mattered greatly for the spread of “emigration fever.” Since the census sheets also listed the number of years during which foreigners had resided in Buenos Aires, the sheets moreover allow us to visualize how migration networks extended in space and time. As José Moya suggested in 1998, with pre-digital methods, “emigration fever” in the Basque Country and Navarra had started in port cities with mountainous hinterlands—exactly the case of Liguria, too. As map 3 reveals, the fever ate its way up from port cities like Genoa, Chiavari, and Savona, into the valleys, down through the Western Po Valley Plain and up again into the Alpes (see map 3).

GIF of birthplaces of the European-Born in the Parish Census of Buenos Aires of 1855, by Length of Residence in Buenos Aires. One dot represents one resident. First Step of GIF: More than 25 years of residence in Buenos Aires. Second Step: 21–25 years. Third: 16–20 years. Fourth: 11–15. Fifth: 7–10. Sixth: 4–6. Seventh: 3 years or less.

The larger question that this particular census brings up is whether it makes sense to classify streams of emigration that preceded the formation of an Italian nation-state as “Italian”. Argentine census takers, to be fair, considered Italy as something more than “only a geographic expression,” as Count Metternich infamously had in 1814: For most people born in what later became Italy, already in 1855, they recorded “Italian” as nationality or “Italy” as country of birth. But they did not always. Franco Garibaldi, for instance, a 25-year-old apprentice from Genoa who had arrived in Argentina in 1850, was, like many of his peers recorded as “Sardinian” (see figure 1). A closer look at the birthplaces of Italian emigrants to Buenos Aires in 1855 reveals that the vast majority came from the Kingdom of Savoy-Piedmont-Sardinia (map 4).

Municipal Birthplaces in Europe of the European-Born in the Parish Census of Buenos Aires of 1855, Overlaid on an 1860 Map of the Kingdom of Savoy-Sardinia.

And the networks fomenting emigration clearly extended into what later became French territory. It was often pre-modern political entities that mattered for migratory networks more than the later nation-states. The case of the Basque-Navarrese region (map 5) was no less clear in this respect. Before it became just that, Italian migration to the Rio de la Plata in fact was not all that Italian.

Municipal Birthplaces in Europe of the European-Born in the Parish Census of Buenos Aires of 1855, Basque Area. Orange Line: French-Spanish Border.